Gabi Seifert

she/her

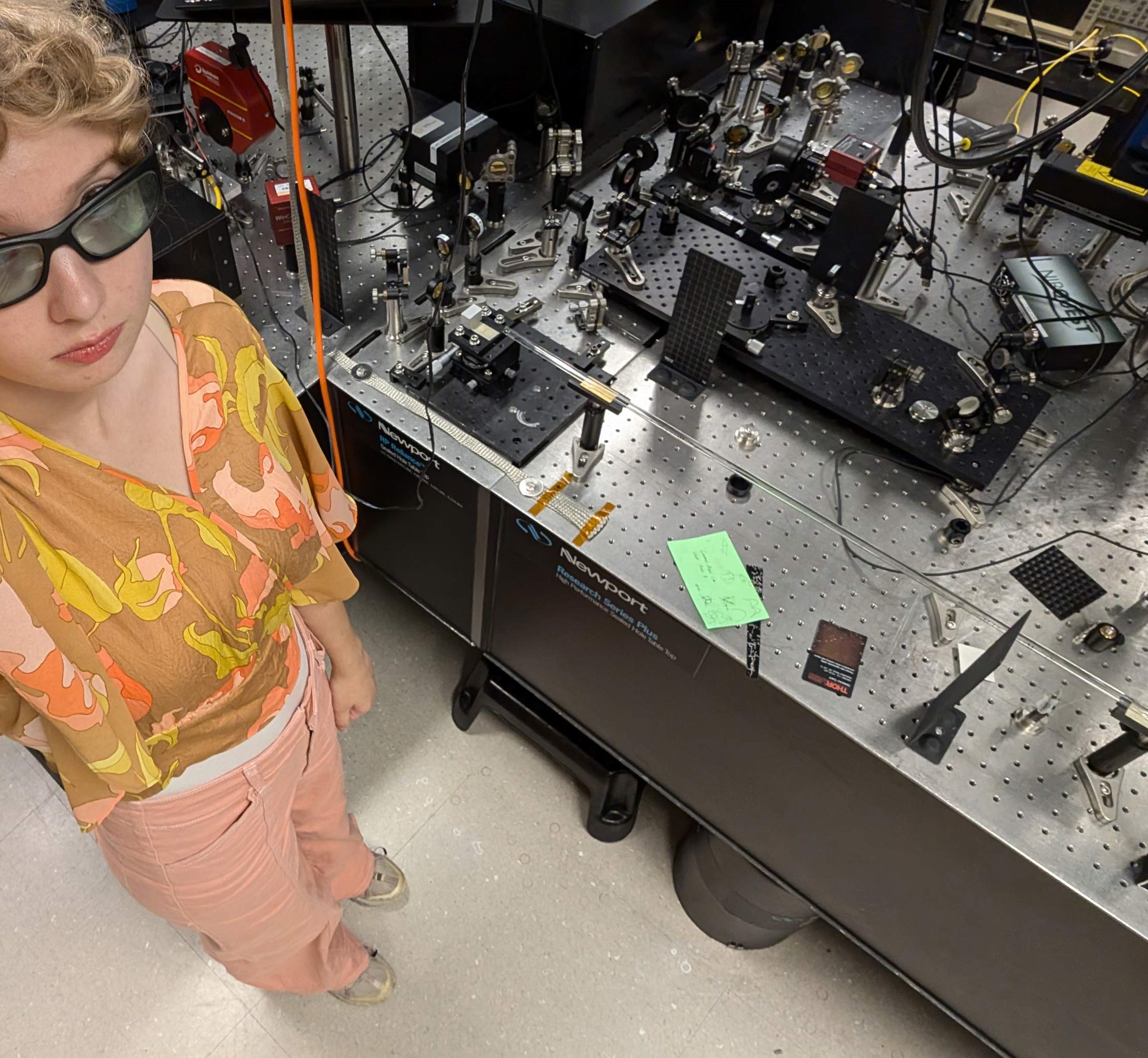

Physics PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder specializing in atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

Physics PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder specializing in atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

Interested in how my lab builds soft x-ray lasers for super high-resolution imaging? Check out our latest paper, where we use high-harmonic generation to produce crazy short wavelengths! Or, if you don't want to sift through all the technical nitty-gritty, my friend Kenna wrote a more accessible article about this experiment! 😄🌈

Hello everybody, I’m Gabi, and welcome to my website! I’m a scientist/artist/programmer from St. Paul, Minnesota, and currently a physics PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder.

In 2023 I graduated from Scripps College in Claremont, California, where I majored in physics, minored in German, and took a variety of classes not related to either of those fields. I'm an aspiring laser cowboy, and my top interests are Enron (a failed energy company credited by Wikipedia as "the largest bankruptcy due specifically to fraud of all time"), amateur website building, Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time as well as other possibly-overdue library books, and artistic pursuits (general).

Look I made it from scratch. I honestly can't believe that people are still surprised by it at this point. What other kind of website could I even possibly have?

The Engine contains: Nothing yet, but soon an explanation of how the train animation works.

Train Car #2 contains: Thoughts on the Poor Image

Prior to the invention of photography in the 19th century, art was not reproducible. Sure, sure, we’ve always been able to paint copies of famous artworks; ancient Greece stamped standardized designs onto coins; and techniques like woodcut printing, etching, and later lithography allowed for limited reproduction. But today we can make infinite reproductions of artwork nearly indistinguishable from (at times, perfect copies of) the original.

So what’s lost? In 1935, German philosopher Walter Benjamin argued that “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be… that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art,” (Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin, 1935).

So artwork has some sort of “aura” that’s lost in reproduction, something inherently tied to the original, its place in history and tradition and culture, its physical presence, its accessibility or inaccessibility to the viewer, that’s lost in reproduction? Why should we buy into any of this bullshit? (Or at least, that’s what we asked Dr. Kevin Vennemann when he introduced our German philosophy class to the concept of an artwork’s aura in the fall of 2022).

He pointed out that we care a great deal about authenticity–that there’s a difference between the print of Van Gogh’s Starry Night that you hang in your living room and the one you wait in line to see at the MoMA, even if physically you can’t tell them apart. There’s a difference between walking along towering sections of the remains of the Berlin wall, watching the way it cuts the city in half, and looking at pictures online.

But pictures online throw a real wrench into Benjamin’s analysis. Can’t blame the guy–he died in 1940. His analysis was a first reaction to the impact of photography, the proliferation of copies among the masses, and the removal of artwork from its historical context of religion and ritual and encroach into politics instead. It’s still deeply relevant, but the internet has changed the ways that we interact with images.

In Hito Steyerl’s 2009 article In Defense of the Poor Image, she defines the poor image as, among other descriptors, “a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. It is… an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution… The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled.”

I first read Steyerl’s article in 2023, in Dr. Daniel Hackbarth’s Metropolis class. We were looking at physical and digital space; the ways that we construct cities online.

You know poor images. We’ve all dealt in them. Who hasn’t watched a pirated copy of The Last Unicorn online, or deciphered a meme through layers of jpeg compression and logos and banners added by seven different reuploaders? They’re omnipresent in our digital landscape, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

To Walter Benjamin, a replication can’t have an aura in the way that an original does. A poor image is defined by that lack, that hole where an aura should be, the immutable distance between it and the original, made up by downloads and uploads and redownloads and reuploads, mechanical degradation and human filtering, its position in space and time far removed from the context of the original.

I’m kind of obsessed with poor images. They’re all wild mythological creatures to me, sailboats on a rough and wild sea, tossed far across the globe every night, transformed and reshaped and dragged from port to port, never alone and never at home. They don’t have an original, or even just one “true” version. There’s no one author. They’re so tied to their particular moment in time, to the technologies and processes that created them that you can’t possibly extricate them from their context. Somehow, these low-quality, jpeg-crunched images have built an aura around themselves when one shouldn’t be possible.

The situation of the poor images “reveals the conditions of their marginalization, the constellation of social forces leading to their online circulation as poor images. Poor images are poor because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images—their status as illicit or degraded grants them exemption from its criteria. Their lack of resolution attests to their appropriation and displacement,” Steyerl writes.

Have you ever seen these things called “stimboards” online? They’re collections of images, usually gifs, with pleasing colors and visuals and motions. Lots of nostalgic aesthetics, slime videos, flashing lights and trailing colors without a clear source. They’re a particularly interesting example of poor images because of the way they proliferate online. I usually find them on Tumblr.

The gentlemanly thing to do when you post a stimboard is to leave a line of credits across the bottom, hyperlinked emojis. Like this:

It’s cute, right? The fun thing about these links is that about 25% of the time, they’re broken. They don’t lead anywhere except a dead URL. The other interesting part of them is that the links don’t usually lead back to what you’d consider the “original” source.

Here’s a typical genealogy: In scary-caregiver’s Star Stimboard post from 2024, they link the source of this starry blanket gif back to a 2023 astrology-themed stimboard by stim-burrow, which links back to 2021 stimboard by helium-stims themed around a French children’s TV series that first aired in 1999. Finally, this post links back to the “original” source: a 2019 YouTube video called “Rubyjam Fabric - Glow Stars Blue” uploaded by an Australian fabric company. It has 176 views.

I followed this set of links in less than a minute, so why does the 2024 poster not just link back to that first video? I think it has to do with the culture of poor images online.

I like to follow these paths back. I like the stimboards. The images are nostalgic, but the nostalgia doesn’t call back to any time other than a nebulous “childhood.” My childhood didn’t look anything like these pictures but I still yearn.

The paths take you interesting places. Instructional videos from the 1990’s. Paint stores on Instagram. An Etsy listing for slime. They lead you through weird corners of the internet you’d never have imagined existed. But often these images don’t even have a real original version anymore. You click through the source lists, post through post through post, and it ends in an uncredited gifset or a TikTok that was deleted or a Pinterest pin with no apparent source.

And even the ones where you find their source, the clipped, sped-up, filtered, 1-second gif is not the original video. Someone grabbed a second and looped it over and over and over again, freezing time, freezing an idea or feeling that’s not part of the original. The little girl in Indonesia who posted a video of her new Aquapets toy in 2013 didn’t know this was going to happen! So what’s the source? What’s the original? Does it even matter? Are these just a part of the fabric of the internet now?

I used to post my art online, back when I was a teenager in the late 2010’s. I remember the first time I ever saw one of my own pieces reposted on Instagram, just noticed by chance as I was scrolling through. I had to do a double take, a wait-that’s-me. That’s my art. Posted by a fan page that credited another fan page that said source: unknown. It drove me nuts and it happened constantly, but at least it was still my original image. Maybe a bit blurry and with the edges cut off, but you could reverse search it, or make out my little artist’s signature in the corner. It hadn’t yet taken on a life of its own, left to sail around eyes on the internet that I hadn’t intended to meet.

But I know that between 2016 and 2019 my art was spread all over the corners of the internet, from Tumblr to Instagram, Pinterest, We Heart It, Reddit, YouTube compilations, Twitter, Facebook, iFunny, reshuffled into memes and reaction videos and fandom archives; and I know that at some point an AI image generator must have scooped it up, scraped it as uncredited training data back when they were first trawling the interwebs. I know my art is built into even those earliest models from 2021, and no matter how many consent boxes I uncheck I can’t pull it out. I think that has to be the final stage of a poor image. Every time I look at an AI-generated artwork, I have to wonder if any of its pixels were once mine.

AI-generated images are sort of the ultimate problem for Walter Benjamin’s idea of the aura of artwork. They simultaneously exist perfectly without history (their artists are no one, their genealogy is lines of code), but also completely trapped within the ideas of a society that made them. AI-generated images are all kind of cliche–they can build fantastic worlds in futuristic, cyberpunk cities, or grand, ancient temples–but it’s all things you’ve almost seen before. Building only with images that already exist, generative AI necessarily cannot make something new or without cultural context. Is this context an aura?

NFT’s did their best to introduce the concept of an “original” of a digital artwork, or at least one “true” version, though I would argue that they had very little success. Take probably the most famous NFT collection–the Bored Ape Yacht Club (so sorry to dredge up pandemic-era memories, I promise I have a point). Like almost all NFT collections, each of these images is procedurally-generated, rather than individually painted by digital artists. Each has various unique features–a hat, a gold chain, a weird background color–pasted over a base image of a monkey. They’re all hosted on the Ethereum blockchain, which means that when you purchase one of these apes for a sometimes-exorbitant price, you get a smart contract that points you to a URL with your image. That’s right! You are a very special buyer and you receive a very special URL! Look, the token even has a unique serial number on the Ethereum ledger! Everyone can see that it’s your image!

This concept of digital ownership and uniqueness is so widely misunderstood and poorly defined that most people don’t even know what an NFT means. Like, it’s an image, and it’s the one true version of that image because… somebody said so? But what if I mint another NFT of the same image on a different currency’s blockchain? What if someone else mints NFT’s of the same image on the same blockchain? How the hell are we supposed to know who the “original” is?

The aura’s lost. There’s nothing there.

NFT’s haven’t really been culturally relevant since 2021 (or financially–a screenshot of the first tweet that sold for nearly $3 million back in 2021 just failed to reach even $300 in a bidding war), but their spotlight in the public eye reveals how concerned we are with what is lost without an original of an artwork–we are all concerned with aura.

So it’s something I like to think about. Can a poor image have an aura? How? Is it different from the aura of a traditional artwork? What do poor images reveal about their origin, the internet as it is today? What do they tell us? And where can I find more of them?

Train Car #3 contains: An Illustrated Explanation of Multi-Pass Cells

Congrats! You found an entire, fully-functioning multi-pass cell in this train car. Someone probably put a whole lot of work into building that…

But hang on. Why should you care? What does a multi-pass cell even do?

I work with ultrafast pulsed lasers. Their pulses are usually about 100 femtoseconds long, which is just about one of the shortest timescales in the universe. For comparison, there are 10^15 femtoseconds in one second. 10^15 seconds is more than 30 million years.

But that’s not enough for us. We want our laser pulses as short as possible, to pack as much energy into one quick, powerful punch as we can. We use a multi-pass cell to make our pulses shorter.

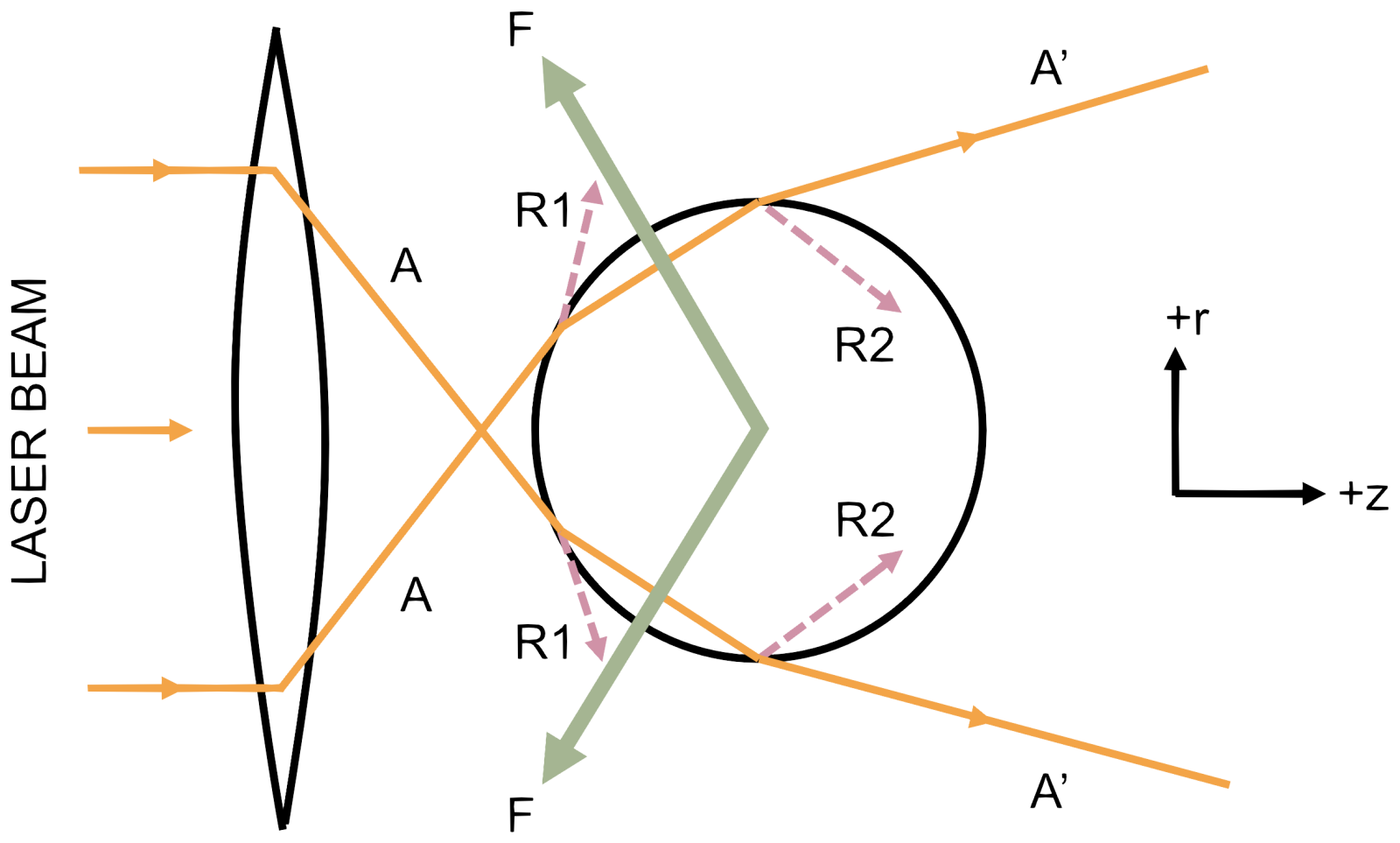

In a multi-pass cell, laser pulses bounce between two mirrors up to dozens of times (we’ve been doing 13 passes of late), going through a calcium fluoride plate in the middle each time. The calcium fluoride plate has nonlinear optical effects that make the pulses a little bit shorter each time. After 13 passes, the laser exits the multi-pass cell shorter than it was before, and we use it for other processes like high-harmonic generation.

So what kind of nonlinear optical effects does this calcium fluoride plate have? How does going through a piece of glass make a laser pulse shorter?

Imagine a laser pulse as a train of photons travelling together. Like this:

The different colors of photons are different wavelengths of light. Red photons are long-wavelength, low-energy light, while blue photons are short-wavelength, high-energy light. All the colors are mixed together in this laser pulse.

The calcium fluoride plate has a property called a X(3) optical nonlinearity. This means that as the laser pulse passes through the material, the strong electric field of the laser changes the optical properties of the material. This produces a nonlinear optical effect called self-phase modulation, which changes the laser pulse by sorting the photons by color:

As the laser pulse passes through the plate, longer-wavelength (red) photons are absorbed and released first, while shorter-wavelength (blue) photons are released last, at the end of the pulse, creating a rainbow along the pulse. In optics, we call this a chirped pulse (imagine a sound that starts with long-wavelength, low frequencies, and rises to short-wavelength, high frequencies–it would sound like a chirp!)

This process actually creates a longer pulse, so we need a second step to un-sort the photons. Luckily for us, at our laser’s wavelength, calcium fluoride has a property called anomalous chromatic dispersion. Anomalous chromatic dispersion means that the blue photons travel faster in the material than the red photons, effectively bringing the blue photons forward and moving the red photons back. Like this:

Essentially, self-phase modulation sorts the pulses into rainbow order, and then anomalous chromatic dispersion pulls the photons back the other way, bringing them all closer together in time, and making the pulse shorter!

This is how almost all pulse compression techniques work, not just multi-pass cells. The great thing about our multi-pass cell is that both of these effects, self-phase modulation and anomalous chromatic dispersion, can come from the same material. That’s only possible because of our central laser wavelength of 3 microns–other wavelengths of light don’t interact with calcium fluoride in the same way, and might use a different material.

It’s also possible to just send the pulse through one thick piece of calcium fluoride instead of doing it over many different passes, but then your optical intensity might get too strong and start activating unwanted optical effects like self-focusing (our laser is already focused! We don’t need more focusing!). Basically, multi-pass cells are an awesome method for pulse compression.

In recent experiments, I successfully compressed laser pulses down from 100 femtoseconds to 20 femtoseconds (wow!). If you want a more technical explanation of that project, check out my multi-pass cell project page:

And in the references section, I’ve linked two articles from the RP Photonics encyclopedia, my favorite optics resource online. Check them out if you want a more mathematical explanation of nonlinear optical effects.

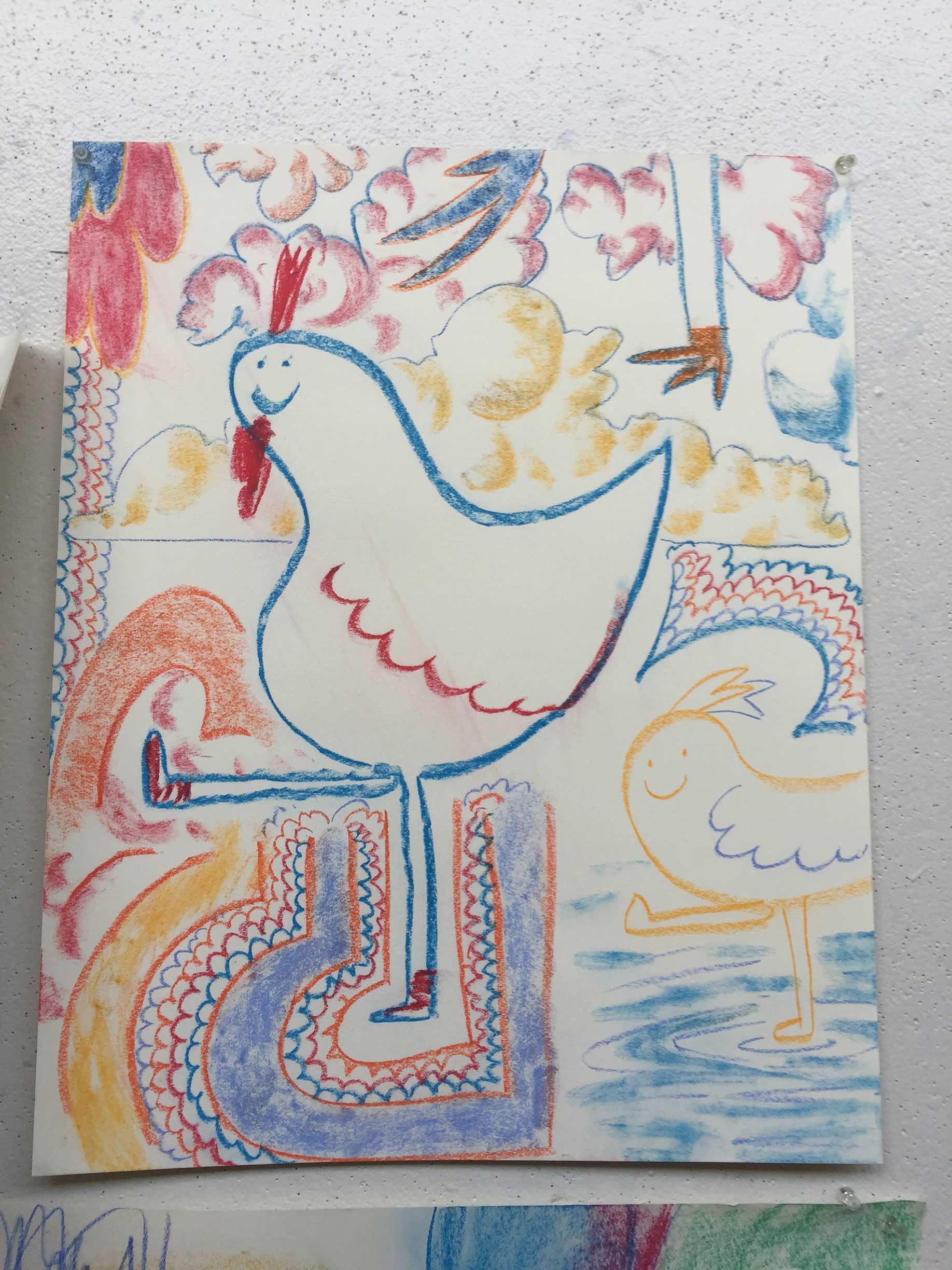

Train Car #4 contains: The Very First Chicken Drawing

Hmm… It’s a little different from all the others. Almost like the person who drew it hadn’t ever drawn a chicken before and didn’t really know what to do with the shape. But this is the image that kicked it all off, in August 2017 (that was the year my family got chickens for the first time).

The chicken drawings have evolved over time, but most still bear a great resemblance to the original. If you want to hear more about my chickens journey, check out my senior speech from highschool.

Train Car #5 contains: An Overdue Library Book

Yikes! Why do you still have Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi checked out? You’ve already read it three times, and you have your own copy. Bring this one back!

I guess Piranesi is just the kind of book that gets stuck in my head. In 2024, it usurped The Elegance of the Hedgehog as my favorite book of all time; I read it in just the course of an afternoon, hunched over its pages in the back of the lab while I was waiting for the spatial light modulator to finish its optimization.

It’s about a man who lives in a world consisting only of an infinite series of grand, empty halls filled with crumbling marble statues and sometimes oceans. If you’re into the fantastical worlds Italo Calvino creates in Invisible Cities, you might like this too. Page 5 reads:

“I am determined to explore as much of the World as I can in my lifetime. To this end… I have climbed up to the Upper Halls where Clouds move in slow procession and Statues appear suddenly out of the Mists. I have explored the Drowned Halls where the Dark Waters are carpeted with white water lilies. I have seen the Derelict Halls of the East where Ceilings, Floors–sometimes even Walls!–have collapsed and the dimness is split by shafts of grey Light.

In all these places I have stood in Doorways and looked ahead. I have never seen any indication that the World was coming to an End, but only the regular progression of Halls and Passageways into the Far Distance.

No Hall, no Vestibule, no Staircase, no Passage is without its Statues. In most Halls they cover all the available space, though here and there you will find an Empty Plinth, Niche or Apse, or even a blank space on a Wall otherwise encrusted with Statues. These Absences are as mysterious in their way as the Statues themselves.”

Mysterious! Compelling! But truth be told, I was already hooked by the two quotes on the very first page. The first:

"I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on." -The Magician's Nephew, C. S. Lewis

The Magician’s Nephew is an interesting entry into the Narnia series, a prequel written five years after the first book, following not the brave and noble Pevensie children of the main series but instead the magician’s nephew himself–a little boy who is no great scholar, magician, or adept, merely the subject. And yet this subject bears witness to the death of one world and the creation of another, perhaps one of the only coherent explanations for Narnia that C. S. Lewis ever feels compelled to supply.

And the second quote:

“People call me a philosopher or a scientist or an anthropologist. I am none of those things. I am an anamnesiologist. I study what has been forgotten. I divine what has disappeared utterly. I work with absences, with silences, with curious gaps between things. I am really more of a magician than anything else.” -Laurence Arne-Sayles, interview in The Secret Garden, May 1976

Piranesi is fundamentally a story about memory, and I’m nothing if not obsessed with the concept of memory. Which is a lifelong preoccupation, by the way–as a kid I used to hold my breath and whisper to myself “don’t forget don’t forget don’t forget”–leaving behind razor-sharp memories of instantaneous moments, climbing into the backseat of my dad’s car, running my finger along the floorboards in the living room of my childhood home, moments stuck in the past as soon as they happened because I was so afraid of forgetting them. Afraid of the past melting and dripping through my clenched fists, losing pieces of myself to the gentle anesthesia of time.

If you’re weird about memory–if you’ve ever read even just bits of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, if you buy madeleines from the bakery in your neighborhood whenever you’ve had an off week just to close your eyes and eat them in tiny bites in the sunlight and imagine the experience catapulting you back to when you still lived in California, back when you ate madeleines with lime-blossom tea in a sun-soaked classroom in the Humanities building with the fountains in the courtyard, the one that used to be an olive grove years before you ever got there, the one where you sat with your friends and made fun of this stupid, ridiculous new app that someone was trying to promote at your school and traded ideas on Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno, if you were so enchanted by the idea of involuntary memory that you decided to create it for yourself on your own terms, if you ever sometimes feel that you might be the Angel of History himself looking back at the wreckage of time and everything that has been lost in horror–then Piranesi might be the book for you.

Anyways. Maybe someone will have returned their copy to the library. Maybe it’s waiting for you.

Train Car #6 contains: A Painting of Silver Glow

Hm. Wow. There’s really a lot going on here, and no I’m not going to explain myself. I will tell you, though, that Silver Glow was one of my favorite toy ponies as a kid, and that dielectric mirrors flash rainbow if you turn them at just the right angle.

If you're interested in more of my digital paintings, I have a whole art archive project page. You can find even more digital paintings in my college newspaper illustrations, or in the translation project for April by Blumfeld.

Train Car #7 contains: The Sticker Store

When I was little, sometimes on very special days my mom would take me to The Sticker Store. They had this wall of receipt-paper rolls of Hambly stickers, tigers and horses and rainbows and birthday cakes and tiny, twinkling stars. In my memory, the whole store is dark and empty except for the enormous sticker wall lit by a single spotlight, although from the review photos online that appears not to be accurate. I was allowed to pick out one sticker roll, and tear one sheet off. I took my time with this impossible decision–faced with all the riches of the world, how could a person choose just one? I fell in love, and I’ve been in love ever since.

The real-world sticker store, Avalon on Grand, was a knick knacks shop in St. Paul, Minnesota full of a riot of greeting cards, toys, gag gifts, jewelry, books, magnets, mugs, disco balls, kooky signs, and oriental rugs. It closed sometime in those odd intervening years after I’d left Minnesota but still stopped through enough that I thought I still knew the city. Maybe Avalon was a victim of the pandemic or of changing tastes. It had always been slightly out of time, even back in 2009 when my mom took me there after school; the Hambly stickers that I loved so much were designed back in the 1980’s, and according to Harry Hambly’s obituary, Hambly Studios closed down in 2012, leaving behind only backlogs of holographic stickers in midwestern tchotchke stores. Carrie's Sticker Collection has the best archive of them that I’ve found online.

At seven years old I most definitely picked the horse stickers every time, regardless of the length of deliberation. Or possibly the unicorns. But I’ve compiled some of my favorites here, crunchy PNGs that I ripped from sticker websites and ebay listings, cropped and recolored to maybe look like real stickers. Feel free to grab some–in this sticker store, you don’t have to pick just one.

Uh oh! The Caboose is locked!

Enter password:

(Hint)

Check out my presentation at the Frontiers in Optics and Laser Science conference in Denver, recorded October 29th, 2025. I talk about my awesome laser pulse compression results with a multi-pass cell, and compare with pulse compression in an anti-resonant hollow-core fiber :D

I've been a member of the lasers team of the Kapteyn-Murnane Group at the University of Colorado Boulder since 2024. We're building a super high resolution microscope using soft x-ray laser pulses produced by high-harmonic generation (HHG). I've worked on optimizing HHG by compressing laser pulses with a multi-pass cell, metallizing crystals for better cooling in regenerative amplifiers, and building out an imaging system with my labmate Will Hettel.

Although I’m interested in a whole bunch of applications of physics, nowadays I mostly work in atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physics. But as an undergraduate, my physics research focused on mathematical analysis of biological systems. In 2020 I started working with Dr. Janet Sheung at Scripps College on understanding iridescence in groups of bacteria or chameleons, produced by grids of cells creating structural color. I LOVED working with light, but didn’t get back to the field until 2022.

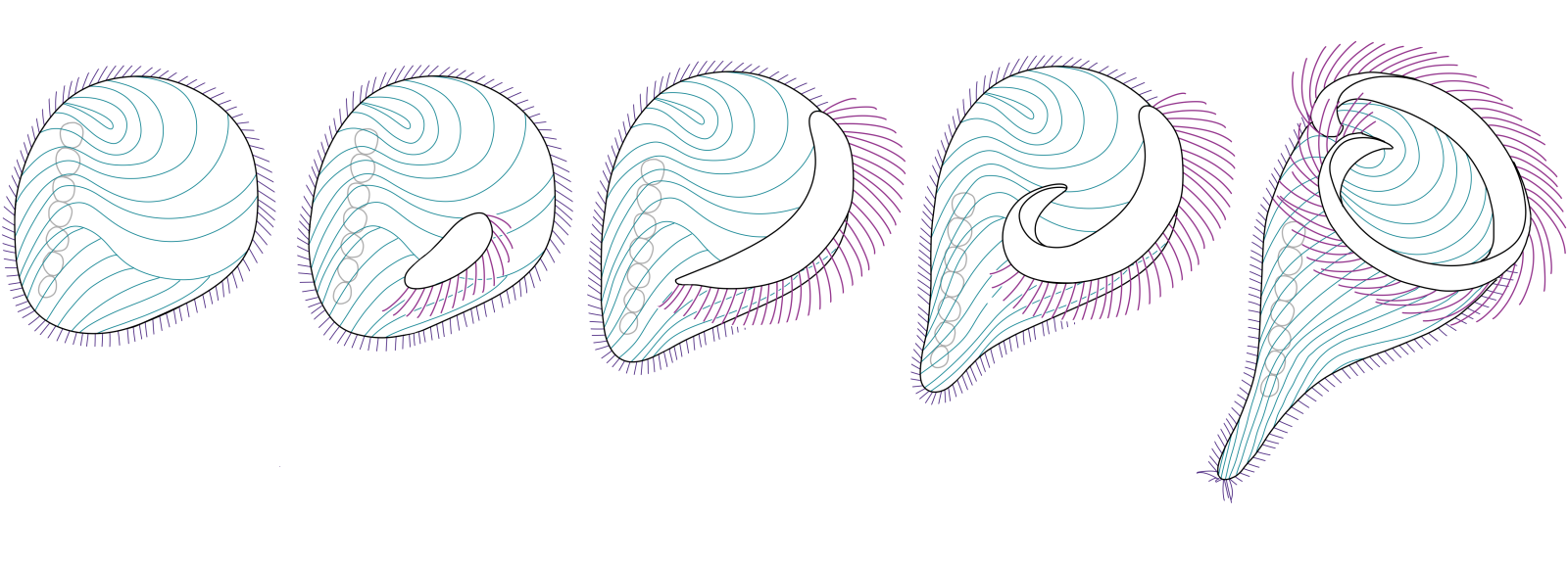

Next I continued working with Dr. Sheung on analysis of motility patterns of single-celled organism Stentor coeruleus during regeneration of the oral apparatus.

Dr. Sheung’s research group was trying to track regeneration by analyzing motility rather than morphology.

I did background research on regulation of genes during cell regeneration, worked on the MATLAB code used for cell tracking, and edited the journal paper, which was published in the Journal of Visualized Experiments. I also made ✨Stentor illustrations✨ for the paper.

Basically, we were chopping off the head of this single-celled organism and then instead of just watching what it physically looks like, we tracked how it was moving around its space to see if it was fully regenerated or not.

After the Stentor project, I moved over to the computational side of physics. Starting in 2021, I began an independent project with guidance from Dr. Sarah Marzen at Scripps College.

Starting with a differential equation, I adapted the equation to fit a model of E. coli predicting the chemical concentration of allolactose in its environment. I solved the differential equation in Python for a single input function, used the Euler approximation to solve it for a vector of functions, used regression analysis to predict all functions, and finally applied the virtual E. coli system to video prediction.

Basically, E. coli networks are pretty good at predicting chemical concentrations in their environment in real life, so I modeled that in Python and tried to get my model network to predict video–it worked ok!!

A paper describing these results was published in Biosystems in January 2024!

Finally, after my forays into biophysics, I was ready to return home to my beloved optics.

I then predicted the force exerted on trapped beads by following the path of all possible rays from a diverging beam incident on a spherical bead in an optical trap. I then summed up all force contributions from input reflection, input refraction, first output reflection, and first output refraction for each ray. This ray analysis in combination with the measured power level of the optical tweezers predicted a net force on the scale of 10^(-13) N exerted on the bead–which matched the measured force!!

For my senior thesis project at Scripps, I built an optical tweezers setup for Dr. Sheung’s lab (it broke a million times but it worked in the end!)

I recently switched over to my permanent domain name, also moving from hosting on Neocities to Github Pages. The Neocities page will remain up, but won't be updated.

Artist:

Artist

Album:

Album

00:00

Duration

music player code based on odditycommoddity's excellent music player. thank you!