Gabi Seifert

she/her

Physics PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder specializing in atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

Physics PhD student at the University of Colorado Boulder specializing in atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

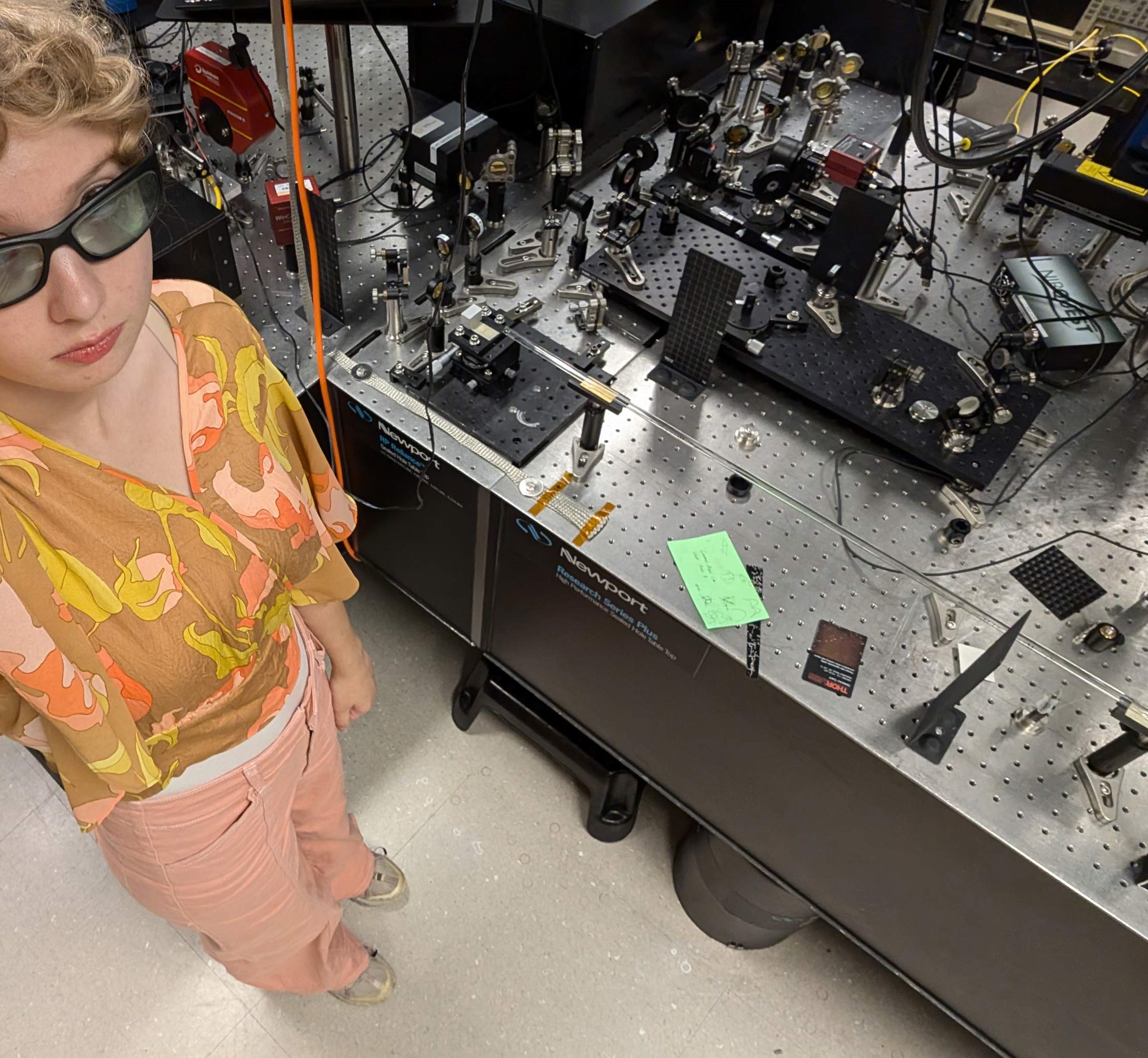

Congrats! You found an entire, fully-functioning multi-pass cell in this train car. Someone probably put a whole lot of work into building that…

But hang on. Why should you care? What does a multi-pass cell even do?

I work with ultrafast pulsed lasers. Their pulses are usually about 100 femtoseconds long, which is just about one of the shortest timescales in the universe. For comparison, there are 10^15 femtoseconds in one second. 10^15 seconds is more than 30 million years.

But that’s not enough for us. We want our laser pulses as short as possible, to pack as much energy into one quick, powerful punch as we can. We use a multi-pass cell to make our pulses shorter.

In a multi-pass cell, laser pulses bounce between two mirrors up to dozens of times (we’ve been doing 13 passes of late), going through a calcium fluoride plate in the middle each time. The calcium fluoride plate has nonlinear optical effects that make the pulses a little bit shorter each time. After 13 passes, the laser exits the multi-pass cell shorter than it was before, and we use it for other processes like high-harmonic generation.

So what kind of nonlinear optical effects does this calcium fluoride plate have? How does going through a piece of glass make a laser pulse shorter?

Imagine a laser pulse as a train of photons travelling together. Like this:

The different colors of photons are different wavelengths of light. Red photons are long-wavelength, low-energy light, while blue photons are short-wavelength, high-energy light. All the colors are mixed together in this laser pulse.

The calcium fluoride plate has a property called a X(3) optical nonlinearity. This means that as the laser pulse passes through the material, the strong electric field of the laser changes the optical properties of the material. This produces a nonlinear optical effect called self-phase modulation, which changes the laser pulse by sorting the photons by color:

As the laser pulse passes through the plate, longer-wavelength (red) photons are absorbed and released first, while shorter-wavelength (blue) photons are released last, at the end of the pulse, creating a rainbow along the pulse. In optics, we call this a chirped pulse (imagine a sound that starts with long-wavelength, low frequencies, and rises to short-wavelength, high frequencies–it would sound like a chirp!)

This process actually creates a longer pulse, so we need a second step to un-sort the photons. Luckily for us, at our laser’s wavelength, calcium fluoride has a property called anomalous chromatic dispersion. Anomalous chromatic dispersion means that the blue photons travel faster in the material than the red photons, effectively bringing the blue photons forward and moving the red photons back. Like this:

Essentially, self-phase modulation sorts the pulses into rainbow order, and then anomalous chromatic dispersion pulls the photons back the other way, bringing them all closer together in time, and making the pulse shorter!

This is how almost all pulse compression techniques work, not just multi-pass cells. The great thing about our multi-pass cell is that both of these effects, self-phase modulation and anomalous chromatic dispersion, can come from the same material. That’s only possible because of our central laser wavelength of 3 microns–other wavelengths of light don’t interact with calcium fluoride in the same way, and might use a different material.

It’s also possible to just send the pulse through one thick piece of calcium fluoride instead of doing it over many different passes, but then your optical intensity might get too strong and start activating unwanted optical effects like self-focusing (our laser is already focused! We don’t need more focusing!). Basically, multi-pass cells are an awesome method for pulse compression.

In recent experiments, I successfully compressed laser pulses down from 100 femtoseconds to 20 femtoseconds (wow!). If you want a more technical explanation of that project, check out my multi-pass cell project page:

And in the references section, I’ve linked two articles from the RP Photonics encyclopedia, my favorite optics resource online. Check them out if you want a more mathematical explanation of nonlinear optical effects.